Dumping on Chester

This past week, the mayor of Chester, Pennsylvania, Stefan Roots, stood in front of the Philadelphia city council and asked those council people to please stop dumping garbage on his city. Philadelphia sends its trash to nearby Chester where it is burned in the largest trash-to-steam incinerator in the United States.

The exhaust from that incineration flows up a huge smokestack and then out over the city. "That gum wrapper on a Philadelphia sidewalk today will be inhaled into the lungs of a child in Chester tomorrow," Roots told Philly's council.

The incinerator, part of ReWorld (formerly known as Covanta), and owned by a Swedish private equity outfit called EQT, also burns garbage from New York City (New York's refuse arrives in Chester via a convoluted transportation chain that includes barges, trains and trucks) and other places, so if Philadelphia stopped sending its stinky diapers and couch cushions and pork chop bones to Chester, the incinerator would still have fuel, but a Philly embargo would make the facility a lot less viable.

I tell the full story of the incinerator, how it came to be located in Chester, the shady dealings, the opposition to it, as part of The Mayor: One Poor City's Fight to Bring Back Government and Save the Nation's Soul, out later this year. Root's face appears on the cover.

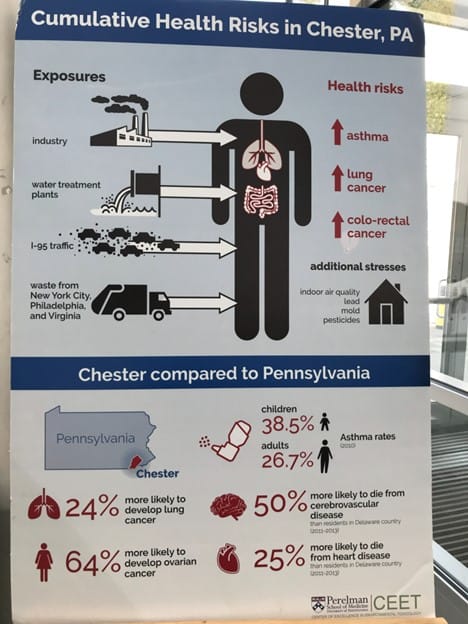

Roots didn't go into all that history in his Philadelphia council appearance. Instead, he appealed to justice. Here's a graphic that explains what he was talking about:

As the chart indicates, pollution from the incinerator is not the only health hazard in Chester. I-95 runs right through the middle of the city. Chester has no doctors. It has no supermarket. It does have a lot of poverty.

Ask any municipal government, any county government, any township government to make a list of intractable problems, and garbage, what trash experts call Municipal Solid Waste, or MSW, will appear somewhere on the list. America leads the world in trash production. In 1960, each American threw out 2.68 pounds of stuff every day. By 2018, each American threw out 4.9 pounds of stuff every day, or 292.4 million tons, and that number is probably growing as more and more of us come to depend upon delivery services, generating all those boxes, plastic wrappers, inserts and stuff we buy but don't really need and wind up tossing out. We are choking on our own trash.

The choking can be literal, as it is for some people in Chester. Incineration was sold in the 1980s as an ideal solution to America's trash burden. All that MSW could be turned into fuel to make steam, to turn turbines, to generate electricity instead of burning fossil fuels, and thus reducing the amount that had to be buried in landfills once all that MSW was turned into ash. But burning trash is hardly clean energy.

According to University of Michigan's Center for Sustainable Systems, MSW incineration produces "CO₂, heavy metals, dioxins, particulates that contribute to climate change, smog, acidification, and human health impacts including asthma and heart and nervous system damage."

The process produces those dangers because the plants burn what Americans throw away: mattresses, plastics, paper, rags, food, shoes... just about everything.

And in Chester, at least, a lot of that fetid waste is carried into the city by an endless stream of heavy trucks barrelling through town on main thoroughfares and down Second Street, now known as PA 291, which also happens to be one of the more dangerous roads in southeast Pennsylvania.

Trash-to-steam has lost its luster. Aging plants are being phased out. One, a Covanta plant in Florida, was wrecked by a fire in 2023, and now the company is being sued by residents who say they were exposed to cancer-causing toxins.

So Roots went into the Philadelphia city council meeting with a good argument. He also knew before he ever made the drive up to Philly that he'd lose the argument on that day. He didn't have the votes. Philadelphia doesn't have a solution ready to replace incineration. But by appearing, by making the argument, he advanced Chester's cause. Philadelphia can no longer say it isn't aware. There will be other votes, and change will happen, though not soon enough for the health and well-being of Chester's residents.

That Roots had to go to the council meeting to plead his case illustrates a bigger issue that affects many places far beyond Chester: Who catches the fallout from American capitalism?

Delaware County, Pennsylvania is home to a lot of wealth. Jeff Yass, the richest man in Pennsylvania, lives in Haverford. (Haverford straddles both Delaware and Montgomery Counties.) Yass is a famous libertarian and a huge donor to Republicans and Republican causes like privatized schools. Radnor, Swarthmore, and other wealthy towns dot the county. A lot of their garbage flowed into Chester.

The ReWorld incinerator is not located in any of those places. It is located in Chester, a majority Black, bankrupt city. That is not an accident.

In a country in which political power flows from financial power, Chester has had little power. The people living in the hollows of Appalachia, who now find themselves with poisoned water from Marcellus Shale fracking operations, who breathe the methane from uncapped and abandoned wells, also have had little power.

But they can vote. There might be something to be gained by paying a lot more attention to the poor places and smaller places and to the people who live in them. Explaining why a poor Black resident of Chester has a lot in common with a poor white Appalachian might seem fruitless. But in my reporting I've found the opposite. Everywhere I've gone the powerless people have a strong sense of their powerlessness and they recognize a brotherhood with others similarly situated. We are seeing right now what can happen when that recognition is shared across racial, geographic, and even cultural lines, and it scares the bejesus out of the powerful.

Comments ()